Today, I am writing about body image, intimacy, and amputation.

As a child, I was bullied relentlessly for my “chicken legs.” One boy used to chant, “Breaker, breaker, jump on her, you’ll break her,” which—looking back—was pretty clever for a third grader, but cruel all the same. Kids clucked like chickens when I walked down the hall. They called me Olive Oyl, Popeye’s homely girlfriend. Those moments stick with you. They shape how you see yourself long before you have the language to understand what’s happening.

Home wasn’t much safer when it came to my body image. My mother and Grammy joked that I had “no ass at all disease,” that my butt was as flat as a cracker. When my mother spanked me, she’d say, “This bony ass hurts my hand.” Those comments landed—and they stayed.

I grew up internalizing the belief that my body was wrong and ugly. When people told me I was beautiful, I assumed they meant only my face or my hair—my naturally curly hair—not my body; they couldn’t mean my body. I was long and lanky, awkward and uncoordinated, like my body didn’t quite belong to me. By my late teens, I was nearly 5’8” and rarely weighed more than 105 pounds, which continued well into my twenties.

I hated my legs—how skinny, long, and stick-straight they were. I did everything I could to hide them. I rarely wore shorts; if I did, it wasn’t out in public, maybe on a hot day in the woods, but not to the store. I lived in long skirts or pants. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, I wore sweatpants under baggy jeans just to make my lower body look less stick-like. When I worked in the car business for 10 years, one of my nicknames was “Stick Chick.” I was constantly accused of having an eating disorder, which hurt deeply because it wasn’t true. The truth was, I could eat whatever I wanted and not gain a pound. I also knew what an eating disorder looked like; my mother was bulimic for my entire childhood, and that was not me.

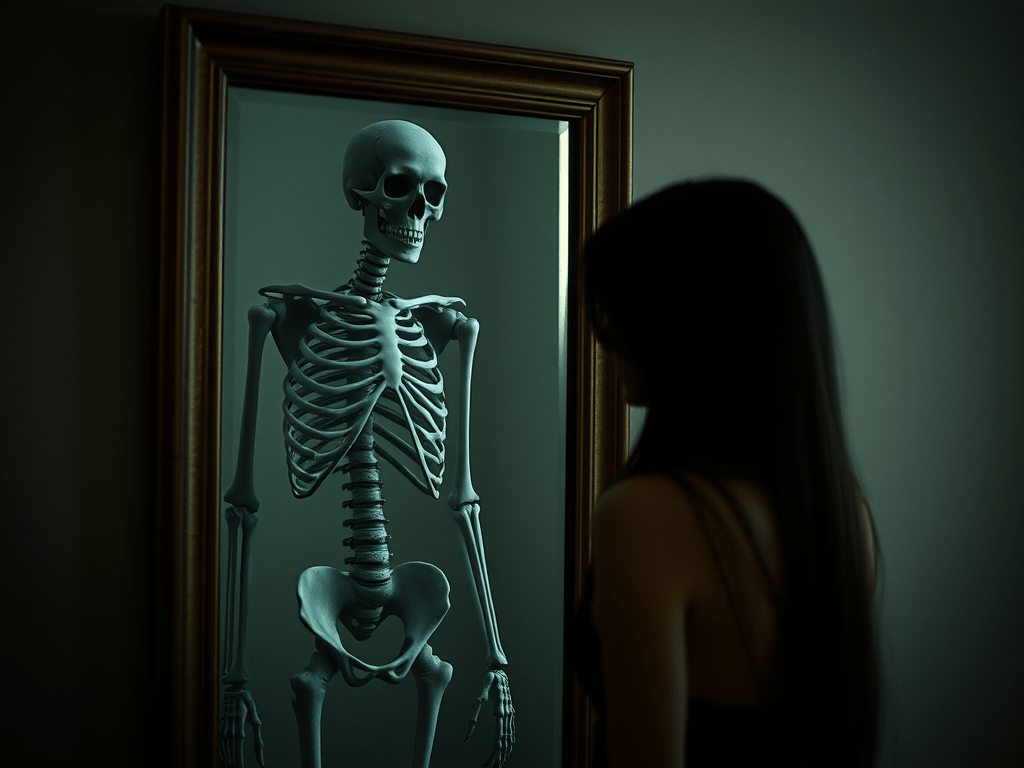

So yes—body dysmorphia accurately describes my younger years. Body dysmorphic disorder involves obsessing over perceived physical flaws, and I absolutely lived with that as a child and young adult. While I still struggle with body image, I no longer meet that definition today.

In 1996, at 22, everything changed. I jumped out of a car traveling 60 miles per hour. The trauma left my right leg permanently disfigured—a compound tib-fib fracture with a visible bone protrusion. For the next 20 years, I hated my legs even more. Not only were they thin, but now one was visibly damaged.

The irony isn’t lost on me that I spent so many years hating my legs—and then eventually lost one.

In my thirties, I drank heavily and was on several prescription medications, most notably Lyrica, all of which caused significant weight gain. For the first time in my life, I was “thick,” and I liked it. At my heaviest, I weighed around 170 pounds. Most of the weight went to my face, belly, and boobs, not much, if any, went to my hips and butt, and nothing to my legs. Around that time, I ran into a “friend” who had always mocked my body. After nearly a decade of not seeing me, she said, “Oh my God, you look like a strawberry with toothpicks for arms and legs.” Even in my thirties, the shaming didn’t stop.

At forty, my life collapsed all at once. I left my second husband and the children I had raised and loved as my own. I went into full menopause. I became ill and lost a significant amount of weight. Just before my amputation, I weighed about 108 pounds and hated how thin I was. I was trying desperately to gain weight, not knowing I had osteomyelitis and that my body simply couldn’t absorb what it needed.

The last time I can remember (I’m sure there have been occasions since, but I remember this one) being mocked for my body was in 2016, just before my amputation. Someone invited me to sit and eat at their crowded table and said, “You can sit in the child booster seat—you’re thin enough.” Thin shaming is just as hurtful as fat shaming and completely unnecessary. No one needs to comment—unsolicited—on someone else’s body. Ever.

At 42, I lost my right leg. I am now deeply grateful for the one intact leg I still have, even though the knee has severe osteoarthritis from 30 years of compensating. I’m very grateful I can walk with a prosthetic. So many amputees cannot. But prosthetics are cold, stiff metal, the opposite of my personal idea of femininity. Add that to the negative body image list.

I’ve always felt pretty in my face and hair. I had great hair when I was young; I still do, though I’ve put it through decades of heat damage straightening it. I’m now eight years post-menopausal, which has honestly been amazing—but it also comes with thinning skin and osteoporosis. The “pretty face” I once relied on now has deep, well-earned lines. Maybe too many for my 52 years. I’ve always worn my emotions on my face. I’m animated. If my mouth doesn’t say it, my face will. That expressiveness—through physical and emotional pain post-amputation—is permanently etched there. I try to frame them as wisdom lines, but it’s getting harder to look in the mirror. I just don’t recognize myself. Selfies are nearly nonexistent these days.

Sexuality has also shifted. As a teenager and well into adulthood, I was very sexual. I enjoyed sex. I loved sex. One might even say I was promiscuous at times. But a couple of years before my amputation—and for a couple of years after—I was celibate. Since 2019, I’ve remained celibate.

About two and a half years after my amputation, I jokingly referred to myself as a “born-again virgin.” I had never been intimate as a one-legged woman. Being without your leg—beneath or beside an able-bodied partner—is incredibly vulnerable. I was terrified. I wanted to do it. I felt I needed to do it. Lose that “born-again virginity” as an amputee.

Thankfully, the person I chose was gentle and kind. I cried quietly because everything was different. He also cried. Positions I once enjoyed were painful or impossible. My body felt completely unfamiliar. The connection with him was brief, but necessary, and I’m grateful for it.

The second—and last—person I was intimate with after my amputation was in 2019. That experience was somewhat traumatic. I was effectively trapped at his home, three and a half hours from mine, without a car. I didn’t learn he was schizophrenic until about two weeks in. I considered spending my last $300 on an Uber just to get home. I eventually managed to get home, but the experience shattered my trust in men.

Since then, I haven’t dated. I don’t trust men—for many reasons. Sex feels complicated. Devotees exist. Disability fetishization is real. My libido is low, likely due to post menopause. My body image struggles remain, primarily because of amputation. If I had the right partner, I might enjoy intimacy again—but I don’t feel driven toward it.

What I miss most is touch. Connection. Not sex itself.

Ironically, my body image has improved since my amputation. It’s not healed, but it’s better. I currently weigh about 130 pounds without my prosthetic, which feels healthy for me. I’d still love another five or ten pounds—preferably in my hips, butt, and legs. In my dream body, I have a thick, curvy lower half. Instead, I inherited my father’s part-German build from the hips down.

And finally, the truth I really haven’t confronted. I no longer believe that finding love is worth the pain. I’ve loved. I’ve been loved. I’ve lost love. Those experiences mattered, and I’m grateful for them. But I don’t believe love is worth the cost anymore. This, coupled with my less-than-desirable body image and distrust of potential intimate partners, keeps me single.

Then again… who knows? When you least expect it, right? Maybe I’ll be a fool and love again.

Thank you for being here.

Please like, comment, share, and subscribe.

Show some LOVE