If no one is there to witness your struggle, is it real?

Imagine going through an amputation completely and utterly alone. No one to hug you. No one to hold your hand. No one to witness your struggle. No one to hold you while you grieve. No one to comfort you in pain. No one to bring you a glass of water. No One – literally. Not metaphorically. Not the loneliness you feel while surrounded by people, but the stark fact of objective reality. THERE IS NO ONE HERE!

For about nine months before my amputation in May of 2016, I was living in a selfless service program, working in the café at a yoga retreat center. I didn’t earn an hourly wage; instead, I received a small stipend, as it was considered a school. In exchange, I lived in a small dorm room in the women’s wing of the ashram.

In February of 2016, after a bone scan through nuclear medicine, I learned that I had osteomyelitis, a serious bone infection that required amputation. My last surgery was in 2012, when I had a total ankle replacement and most likely when the osteomyelitis originated.

I chose a surgery date in May, which gave me about twelve weeks to get my life in order. I needed to move. I needed somewhere accessible and affordable, since I had been on Social Security Disability for about six years and had minimal income.

The housing I found was about 55 miles away from the people who had become my community at the ashram/yoga retreat center in the Poconos. It was a double-wide modular home that had been divided into two apartments. I lived in the back unit, which was the original primary bedroom with an attached bathroom. That room functioned as both my bedroom and living room, and I had a small, charming kitchen. I loved the space. The only downside was the distance from my new people.

At that time, I had been estranged from my mother for about five years and had no contact with her. Our last interactions included phone conversations in which she told me she wished I were dead because life would be easier. We stopped speaking entirely. My younger sister and I were also no longer in contact. To this day, I don’t fully understand why. I know my volatile relationship with our mother put her in a difficult position, and I understand her loyalty to our mother since she has always been close to her. However, I still struggle with the sense of abandonment.

I was also without my second husband, though we were still legally married; we had been legally separated since 2013. I hadn’t seen or had any contact with my (step) children in over a year by the time of my amputation.

During the twelve weeks leading up to surgery, I had extraordinary support from an older holistic pharmacist and his wife, who helped prepare me physically, emotionally, and spiritually. They gave me loving parental comfort. The surgery and recovery were the smoothest I had ever experienced: no infections, no complications, which was remarkable given my long history of surgeries with complications and infections. Unfortunately, that relationship imploded while I was still in the hospital over the use of cannabis for pain management.

Leading up to the amputation felt like a doomsday countdown, even though I was ready to let go of the trauma, pain, infections, and toxicity associated with my leg. I had faced the possibility of amputation three times over the previous twenty years. By this point, I had been mentally ready for it for several years, and the timing felt right.

Despite the complexity and loss surrounding that period, it was ultimately a beautiful experience of release. Still, the fear leading up to it was intense. Everything I thought I knew about amputation after twenty years of research turned out to be completely wrong.

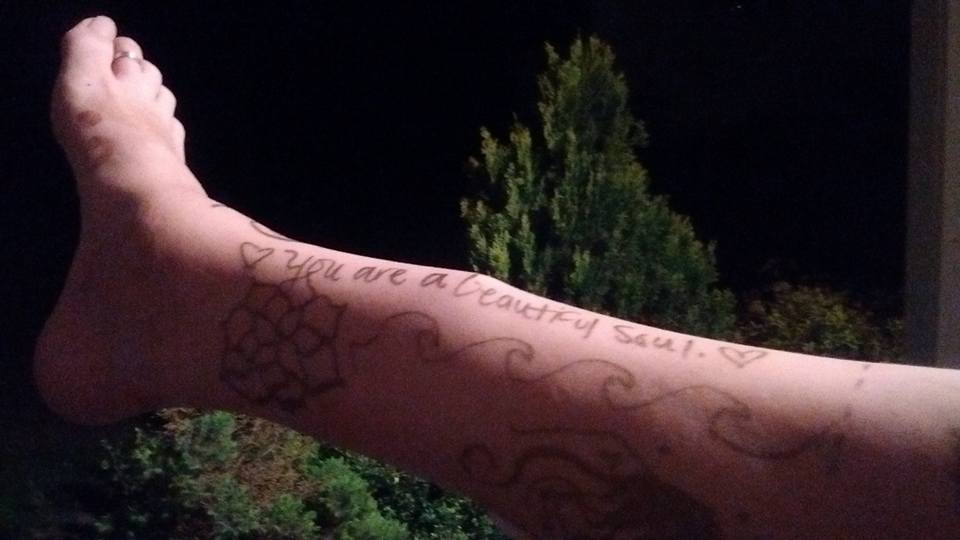

The night before surgery, I had a wonderful dinner with friends. We drank, laughed, smoked cannabis, and covered my leg with drawings, jokes, words, and sacred geometry. It was joyful and meaningful. I stayed that night with my favorite person.

The next morning, Thursday, May 12, the older couple picked me up and drove me forty-five minutes to the hospital for the scheduled below-the-knee amputation of my right leg.

I remember being taken back to surgery prep. I sat on the bed and held my tiger iron crystal; my favorite person gifted it to me, which went into surgery with me as a “religious talisman” and was placed under me during the amputation. I sat and had the most beautiful meditation before getting IV’d and all the pre-surgery procedures. This surgery was the best surgery I’d ever had—and by that point, I’d had dozens. Every prior surgery had come with complications and infections; this one didn’t. I truly believe that the drastic lifestyle changes I made beforehand, along with the support of the holistic pharmacist and his wife, made an enormous difference in my physical healing.

Before the amputation, I did a long cellular healing hypnosis session that lasted for hours. It wasn’t recorded, so I don’t know exactly what happened during it, but I know it mattered. I also did bioacoustic healing with a budding practitioner at the yoga retreat center where I was living. I healed beautifully. My surgeon did an excellent job, and I was only in the hospital for six days.

Three days post-amputation, I wanted to come off morphine. I had warned everyone in my life long before that morphine made me a nasty human being. My amputation was on a Thursday, and that Sunday, I told my nurse I wanted to stop taking it. She was at her portable computer, typing, and whipped her head around and said, “Are you sure?” I said yes.

She suggested Dilaudid, and I told her no—that it was one of my allergies. She laughed and said she would have known that before giving it to me, since it was clearly listed in my chart. Dilaudid causes me anaphylactic shock—my throat swells, I can’t swallow—and it’s terrifying. She asked what I wanted instead, and I said Vicodin. She didn’t think it would be enough. I told her it would be, that it affected me the way morphine should, and that I was a much nicer person on it.

So I switched to Vicodin. I was still receiving blood thinner injections in my stomach. None of it helped with the phantom itching (the worst), stabbing, electricity (think high voltage taser), all my new life-mates. All unbelievable mind fuckery!

I was still on my husband’s Department of Defense health insurance—we were legally separated—and while I was still heavily medicated, a woman came into my hospital room and essentially sold me on a rehab facility. It felt like a sales pitch. She left me a brochure, and I agreed to go because it was close to the yoga retreat center, so my people could visit.

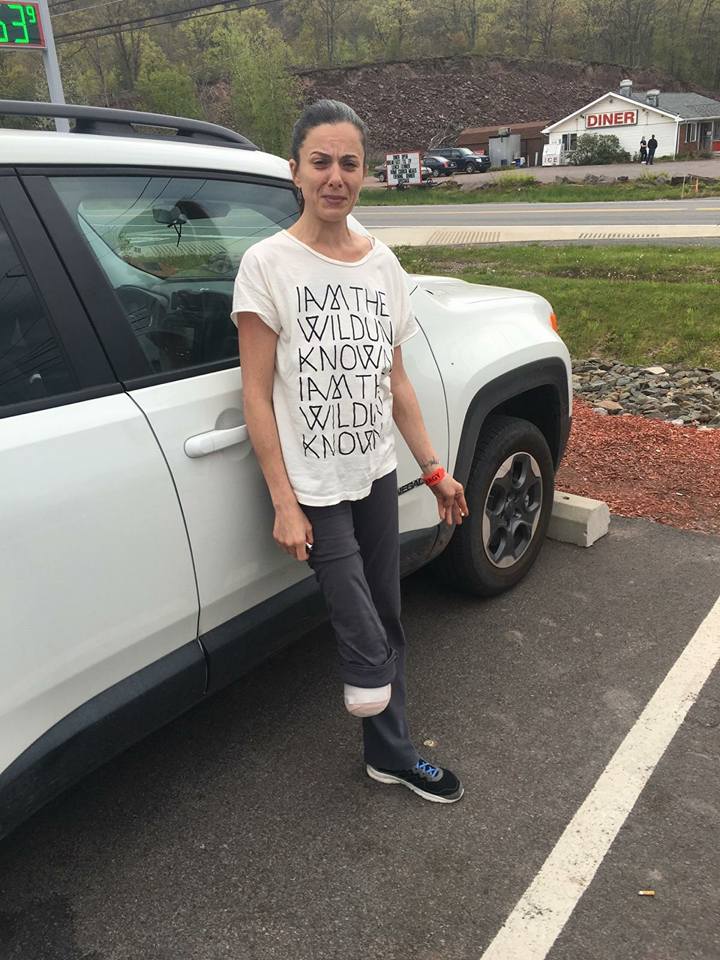

Six days post-amputation—Wednesday, May 18—I was transported to the rehab facility in an ambulance-like transport van. When I arrived, I asked for a walker. They gave me a walker with no wheels and walked me a long distance to the back of the building, where my room was.

It was a shared room. When I looked into the shared bathroom, I was horrified. There was feces smeared everywhere—on the walls, the toilet, the sink. I asked what the hell I was looking at. They told me my roommate was a “known feces smearer.”

INCREDULOUS! I was six days post-op from a below-knee amputation. I was not staying there! I started hopping toward the front desk using the walker, furious, shocked, and disgusted. At the desk, they told me that if I left, it would be against medical advice, and my insurance might not pay. I told them I hadn’t signed a single piece of paperwork and had been there for seven minutes—they couldn’t bill anything.

I asked where I could smoke. They said I could smoke in the grass near the field by the road, but I wasn’t allowed to take the walker off the porch. So I left the walker behind, hopped into the grass on one leg, and scooted myself on my butt about a hundred feet into the field. Thankfully, it was May.

I called and texted my favorite person and a few others. My favorite person couldn’t get to me for about three hours due to work. I sat there rolling lavender, mullein, and lobelia cigarettes, desperately wanting nicotine. I had quit smoking to help my bones heal—something I’d never done before any previous surgery.

When he finally arrived, he was panicked. I had no walker, no crutches, nothing. I hadn’t been formally discharged—I’d been transferred from the hospital to rehab, where I was supposed to receive mobility equipment. I got none of it. I made him stop anywhere so I could get a pack of cigarettes. I was not ok.

We went back to the hospital where I had just been discharged, looking for some type of mobility device. No one would give me a walker or crutches. To this day, I’ve never officially complained about any of it, though I probably should—even nearly ten years later.

Before my amputation, I’d attended one amputee support group, but I’d been turned off by the political tone and lack of supportive energy. Still, I called the group leader and explained what had happened—that I was going home instead of rehab and had no mobility aids. He said, “I’m bringing you a walker.” And he did. That small act was life-saving.

We returned to my apartment, which wasn’t ready for me at all. Area rugs were everywhere. My favorite person rolled them up, cleared paths, and set me up as best he could. Later, he told me that night was the most scared he’d ever been for me, leaving me alone, fifty-five miles from anyone, with no car, no license, no neighbors I knew, no groceries, and no leg! I wasn’t supposed to be home yet. I was supposed to be in rehab for weeks.

He eventually left, and I was alone—this was before grocery delivery, before Zoom, before all the systems people now rely on. I had no contact with the holistic pharmacist and his wife since 3 days post-op in the hospital, which made me very sad. It was just me, freshly amputated, figuring out what the fuck to do, completely and utterly ALONE!

I have lived alone six days after my amputation, almost ten years. No witness to the highs and lows, no comfort from another human, no help—no one. The first seven months were the hardest. I often went, on average, two weeks without a visitor because my apartment was far from my friends, many of whom did not have cars. I suffered a fracture on the fibula of my residual limb, five weeks to the day post amputation, which complicated everything, including fitting a prosthetic. I was going through full menopause, divorce, and amputation all alone and simultaneously. Those months changed me profoundly: I was transformed through a combination of grace and grit.

Please like, comment, share, and subscribe to my blog. Thank you for being here.

2 responses to “No Witness”

-

It’s incredible what you have accomplished while healing from your amputation. I have been in awe of you since the first time I came across your IG account and we became friends. You are one of the strongest people I know. Your ability to hold every emotion and move through it is masterful. Thank you for all that you have taught me 🙏

-

It’s a beautiful experience to have a reciprocal friendship full of support, compassion, generosity and genuine love. Thank you for showing me that. I love you, dear friend.

LikeLike

-

Show some LOVE