Today, I am writing about my experience with prosthetics, the people who make them, and the incredibly flawed health care system in the United States.

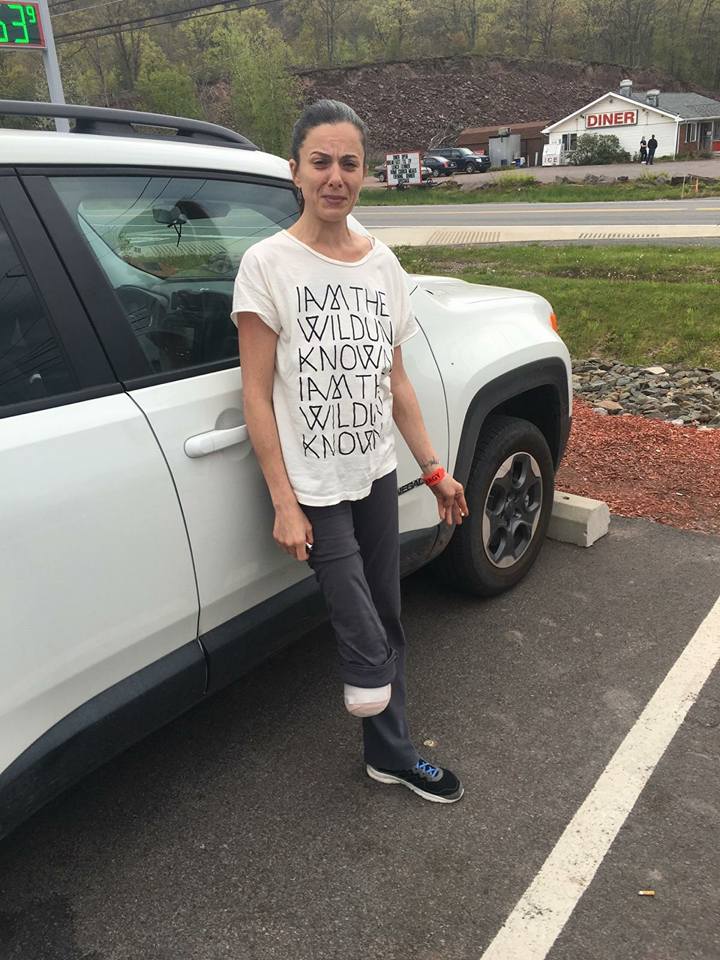

I became a right below-knee amputee in May 2016.

First, what is a prosthetist?

A prosthetist is a specialized healthcare clinician who designs, fabricates, fits, and maintains artificial limbs and orthotics. Certified Prosthetist and Orthotist (CPO).

They work with people who have limb loss, injury, or congenital differences, helping to restore mobility and function.

They typically complete a two-year master’s program, followed by a residency, to become certified. Prosthetists are not doctors; they are clinicians with “advanced”, specialized training.

Prosthetists are paid well, considering they only need two years of formal education. As of 2026, the median salary ranges from about $78,000 to $88,000 per year, with high earners in large or national clinics earning $150,000 to $200,000 annually.

It’s a lucrative business.

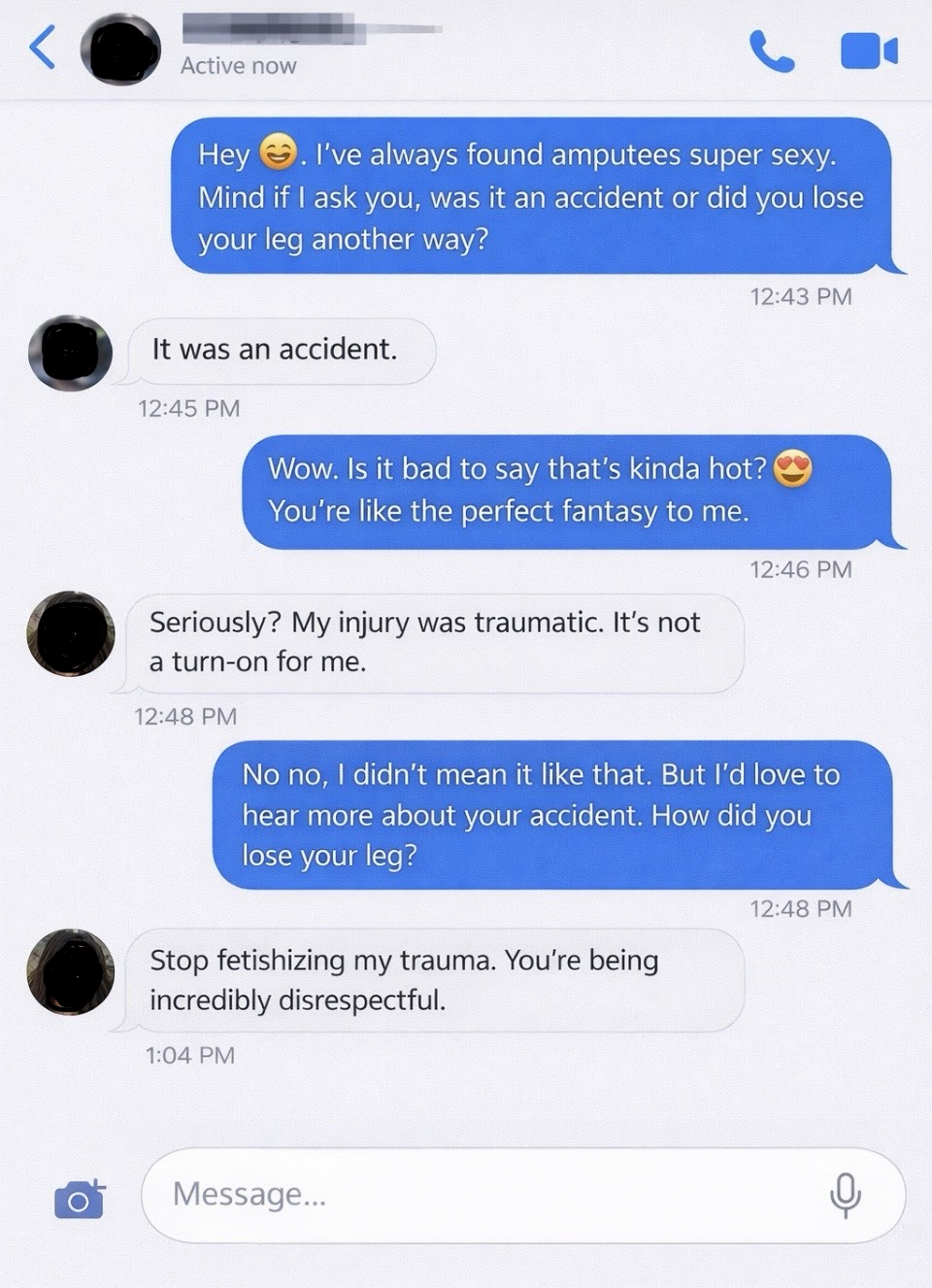

I strongly believe every prosthetic clinic should employ people with lived limb-loss experience, both upper and lower limbs. Nothing replaces lived knowledge. You can study limbs, but living without one is different. It’s like going to a male OBGYN or a female urologist for prostate health.

I have literally pointed to every intact leg in an exam room and said, “You don’t understand, you don’t understand,” And while pointing at my intact leg, “I didn’t understand,” and pointing at my right residual limb, “now I understand”.

Prosthesis or prosthetic?

I personally prefer the word prosthetic over prosthesis—the latter is a mouthful, and frankly, I’m not a fan of how it sounds. Technically, a prosthesis is a noun that refers to a physical artificial limb. Prosthetic is a descriptive adjective. I use the word prosthetic as a “shorthand” noun for the device itself.

My first experience with a prosthetist. June 2016.

His name was Tom, but I called him “Tommy Two Times” to my friends, like the character, Tony Two Times, in the movie Goodfellas.

Tom always repeated himself because he clearly wasn’t confident the first time. He was literally learning as he went.

He was in his residency. While he technically had a supervising CPO, that supervisor wasn’t always present, if ever. I spent a lot of time sitting in exam rooms—without a leg—waiting while Tommy Two Times learned to be a Prosthetist.

Simply put: he didn’t know what he was doing.

I understand learning curves. I understand being new. But no one should ever be an unwilling guinea pig.

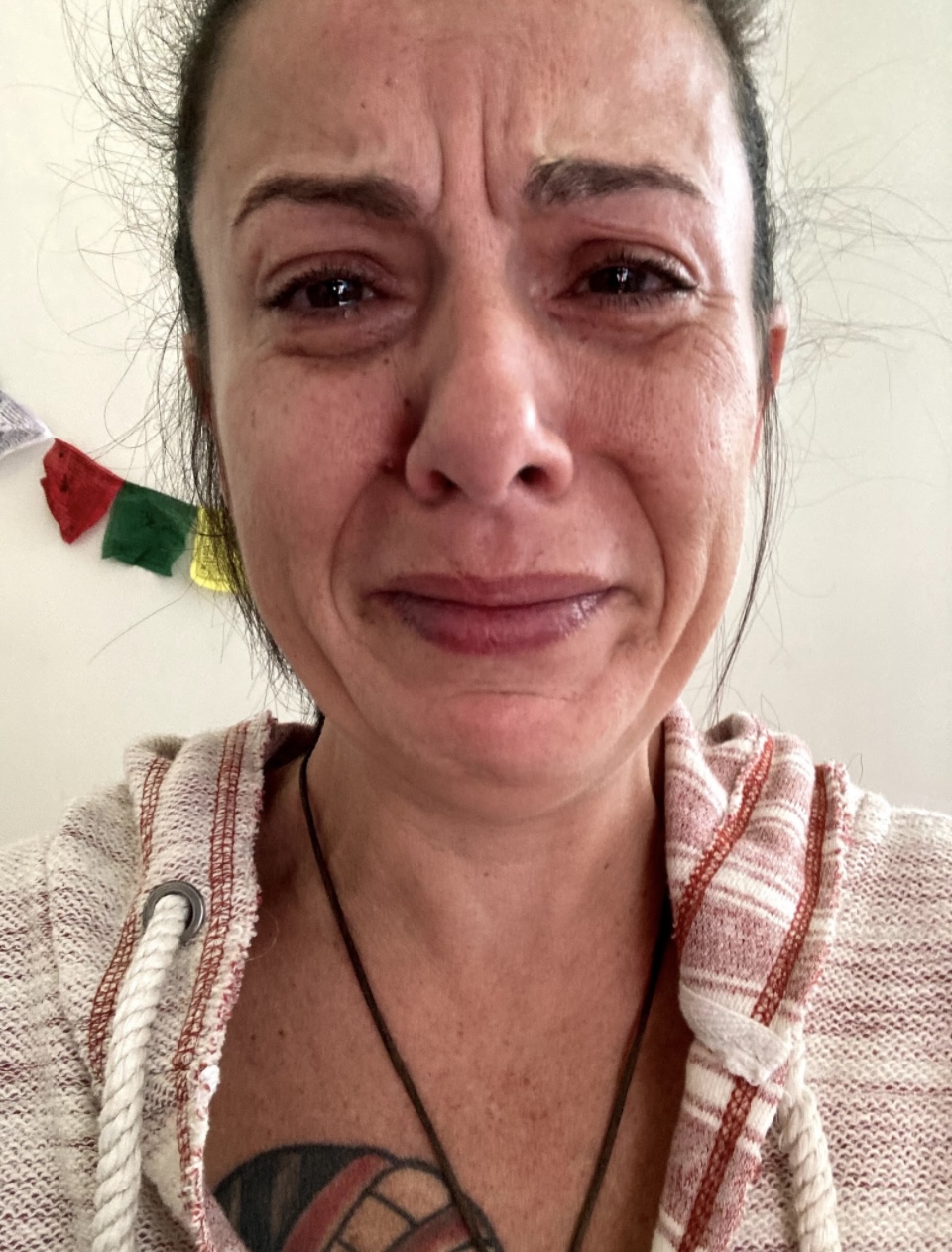

Five weeks to the day after my amputation, something happened that changed everything at the time.

A UPS delivery driver banged on my door like there was a fucking fire! I had been asleep during the day because of horrific nighttime phantom pain that kept me awake all night. Startled awake, my 42-year-old brain forgot I only had one leg.

I rushed up out of bed to run to the door. Frightened and not completely awake, I went straight down, directly onto my residual limb!

The pain was beyond anything I had experienced—including the amputation itself.

I called my surgeon.

I called my prosthetist.

No one suggested an X-ray. There was no bruising. No major swelling. So no one suspected a fracture.

For the next three weeks, I tried to walk with an early temporary/test prosthetic while unknowingly having a fracture at the tip of my tibia.

The prosthetic itself looked horrifying—like a misshapen mummy cone, it didn’t even remotely resemble the shape of a residual limb.

I was told to walk, to bear weight.

I couldn’t. I was terrified and depressed, thinking I’d never walk in a prosthetic.

Three weeks later, I finally got an X-ray—which was literally upstairs from the prosthetist’s office—that revealed a two-centimeter fibia fracture at the very end of my residual bone.

I felt relief, knowing this was not permanent; it was something that would heal. At least there was a reason for the pain and inability to bear weight while wearing a prosthetic.

But that diagnosis delayed my walking with a prosthetic for another 12 weeks. By the time healing was complete, I was nearly six months post-amputation.

After healing (with the help of time and daily comfrey poultices), I fired Tommy Two Times.

When I met my second prosthetist, they told me Tommy Two Times had put me in the wrong foot size—a size 9 prosthetic foot shell when I am a true size 8. I never understood why I couldn’t fit into any of my shoes. I actually cut the heel opening of a few shoes so the foot would fit in the shoe. I assumed that was just “how prosthetics were.”

That discovery alone still makes me angry.

This new prosthetist was from a well-known national clinic. I worked with a father-daughter team. The difference between Tommy Two Times and this team was night and day.

They gave me a prosthetic I could actually walk in.

It was beautiful. It fit. It didn’t hurt.

In April 2017—11 months after my amputation—I finally walked pain-free.

It was literally life-changing.

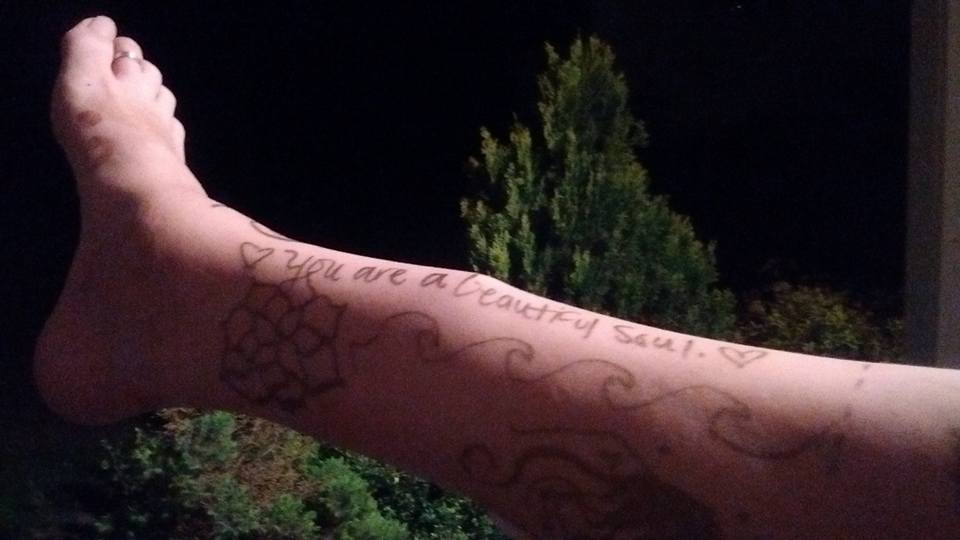

When I received that first functioning prosthetic leg, I chose to honor that moment with a healing ceremony—a pure (tested) MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) assisted meditation.

I took a therapeutic dose of MDMA (also known as ecstasy) and intentionally created a safe, calm, and nurturing space. I meditated with my new prosthetic leg on for hours, returning again and again to the same sacred intention: this was my new reality, and this is how I would walk through the rest of this lifetime.

The following day, I wore my prosthetic leg for 15 hours, and it felt nothing short of miraculous. From that point in April/May 2017 until September of 2018, I was able to bartend, lightly jog, hike, climb rocks, leap over small creeks, and reconnect with a sense of freedom in my body. I moved with confidence and trust—until my “compensator” knee eventually gave out.

I truly believe that the MDMA-assisted meditation softened and opened my psyche, allowing me to fully accept life with a prosthetic limb—not as a loss, but as a continuation. It helped me surrender to the path I was on and embody the truth that this is how I would move through the world. In many ways, that moment set the tone for how I have walked—physically, emotionally, and spiritually—ever since.

In June 2017, I moved to Maine. I stayed with the same national prosthetics and orthotics chain and transferred to a clinic in my area.

Reminiscent of Tommy Two Times, I encountered another prosthetist with whom I didn’t connect; he felt more like a car salesman than a clinician. I didn’t feel heard, so I left him after almost two years.

Through Instagram, I connected with a lower limb amputee who was a prosthetic fabricator at a small, local, family-owned clinic.

In 2019, they built the socket I still wear today— having a lower-limb amputee involved in that process made all the difference.

Unfortunately, in 2022, that clinic stopped accepting insurance entirely. Self-pay prosthetics are simply not realistic for most people, certainly not me.

Without options, I returned—again—to the national clinic, this time a different location.

Thankfully, I like my current prosthetist; he listens to me, respects my self-advocacy, and treats me like a human being who knows more about limb-loss than he does.

Unfortunately, the local clinic location closed in 2025, which was less than 5 miles from my home. They consolidated offices over 30 miles away, which is a challenge when you need quick adjustments or emergency help. But it’s the closest one in my area.

I don’t love that one large chain essentially has a monopoly in Maine. Choice matters—especially in healthcare.

But I’m fairly content with my current prosthetist.

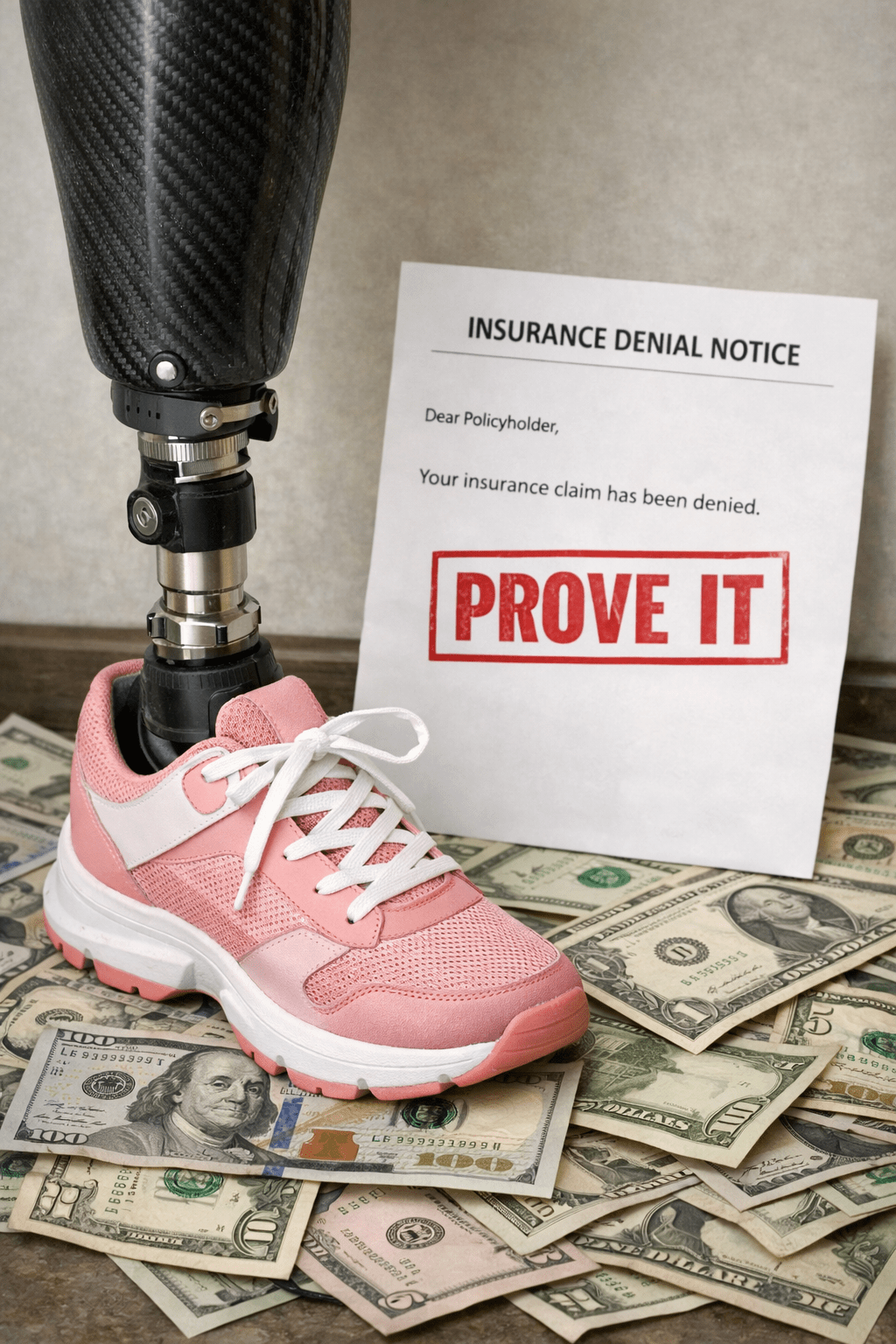

And finally, let’s get into the fuckery that is health insurance and Medicare in the US.

Because I was still technically married at the time of my amputation in 2016, I was covered under his Department of Defense health insurance plan. That insurance paid for my amputation and most of my first three prosthetics.

When I moved to Maine and received my second functional walking leg, I was told my copay/out-of-pocket deductible would be over $5,000. The clinic advised me to contact the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, which helps people return to work and can cover costs not covered by insurance for mobility devices.

Vocational Rehab agreed to cover the out-of-pocket cost, but only after I secured employment and worked for 90 days. I found a bartending job on my own—something I never thought I’d return to—and worked for five months and met that requirement.

Once I met that out-of-pocket deductible, I no longer had to jump through bureaucratic hoops to receive prosthetics in the future.

The clinic also allowed me to receive the leg before the payment was completed, which made it possible for me to work those three months in the first place.

In December 2020, my divorce was finalized, and I was no longer on his health insurance. I switched to Medicare, which has been great regarding zero copays and deductibles.

Walking itself is often deemed “not medically necessary”, especially when it comes to “advanced” components—like ankles that move, knees that function properly, or technology that mimics a natural limb.

Denials are very common. Preauthorizations are exhausting.

Medicare imposes caps and restrictions.

You must prove, repeatedly, that a prosthetic leg helps you… walk.

Let that sink in.

PROVE A PROSTHETIC LEG HELPS YOU WALK! INCREDULOUS.

Overall, I walk well in my prosthetic. I have a significant limp since 2018, and it’s not because of the prosthetic; it’s because my intact leg’s knee has severe osteoarthritis; the orthopedic surgeon called it “the knee of an 80-year-old retired marathon runner.” I have also pulled my ACL in that knee a couple of times since my amputation.

But I refuse to have my knee replaced because joint replacement in my ankle caused osteomyelitis, which was the final complication that led to my below-knee amputation. I have no desire to replace my knee on my intact leg, risking infection and potential amputation, losing my knee on that leg.

NO THANK YOU! I’ll continue to be gimpy.

People always seem to comment on how well I walk in a prosthetic. My response is always, “I’d walk better and possibly run if I hadn’t compensated for over 20 years on my left leg before amputation; my good leg is my prosthetic.”

I often think about waiting twenty years to amputate. What was I so afraid of when the potential for amputation was on the table, three official times in those twenty years?

I did everything to avoid amputation, all the while unknowingly damaging my “compensator” knee.

Hindsight.

It’s been quite an amazing journey to get where I am today.

I’ve had six different legs, six feet, and five prosthetists. I’ve been in the same socket (which holds your residual limb) for almost seven years.

I’m considered “lucky” to not need new sockets all the time; most amputees experience fluctuations in residual limb size, which complicates wearing a socket. Thankfully, I haven’t experienced that since the first two years post-amputation, when the residual limb changes significantly in size as it heals.

The only issue I really have with my prosthetic is sweat and blisters. In the blazing summer heat, it can get so sweaty in the silicone liner that my suspension system will lose suction; if I gently shake my leg or continue to walk with my prosthetic, the leg will fall completely off. Incredibly dangerous.

Just a little sweat causes friction, and the friction, combined with skin and silicone, creates blisters. They are very painful while wearing a prosthetic.

There isn’t much I can do once I have a blister, except keep my residual limb dry and let the skin heal. Which means, leg off. That’s a significant challenge: living alone with zero assistance and a dog that needs to be walked every day. I do not use a walker, crutches, or a wheelchair anymore. So, all day, it’s leg on, leg off.

Despite the challenges, I express my gratitude daily for being able to live independently and walk my dog. It really is that simple.

Thank you for taking the time to read.

If you feel inclined, please like, share, comment, and subscribe.

Leave a reply to Tristan Burgess Cancel reply